I cannot remember exactly when I first met Michael Sporn. In the mid-1970s I began attending events given by ASIFA-East, and I’m sure that’s where I met Michael, but I couldn’t name the event or the year.

Certainly, I knew him by the time he was working on Raggedy Ann and Andy in 1976. I began working in the animation business that year. Michael was 8 years my senior and while farther along in his career, he was close enough to my age to be accessible. His love for animation was obvious from the first time I met him and he was always happy to share his knowledge.

While American animation was born in New York, its survival there was tenuous from the 1930s onwards. The Fleischer studio left for Miami and later returned under new ownership. The Van Beuren studio went out of business. Paul Terry left the city proper for the suburb of New Rochelle. As theatrical cartoons died in the 1950s and ‘60s, New York survived on TV commercials with longer projects appearing only occasionally. The artists in N.Y. animation were older, pretty much all veterans of the theatrical studios. Some had entered the industry as early as the 1920s and others as late as the 1950s, but the industry wasn’t steady enough to entice newcomers except for those who loved animation deeply. There were many better ways to earn a living as an artist in New York when Michael entered the business.

By the time of Raggedy Ann, Michael had already worked for John Hubley, someone who influenced Michael deeply. Hubley was a pioneer in breaking the monopoly of the Disney design style, which he continued to do at UPA and at his own studio. He also gravitated to projects that were far from typical in animation. His films with his wife Faith dealt with childhood from a child’s point of view and with the politics of nationalism and the arms race. Michael continued the Hubley tradition of eclectic design and films that were socially aware.

I think the two best words to describe Michael were courage and determination. It took both to brave the uncertainty of New York animation and to make films that he felt a personal connection to. The majority of N.Y. studios were content to do service work and satisfied if they could keep their doors open. Michael, from the beginning, sought out projects that were off the beaten track and that he could invest in emotionally. At the same time, Michael was always aware of the audience. While many artists succumb to self-indulgence, Michael was always interested in being heard. His films were always accessible.

Many of the New York studios were prejudiced against younger artists. Many of them also ignored the better veteran animators who were available. Michael embraced both. He was constantly giving young artists opportunities, many of whom went on to productive careers in and out of animation. Animation lovers owe Michael a debt of gratitude for keeping the late Tissa David busy and giving her opportunities like The Marzipan Pig, a half hour special she animated in its entirety for him. Other veterans such as Dante Barbetta also found work with Michael.

Like many young animators, I left New York after a few years in search of work, but I always kept in touch with Michael and visited him whenever I was in New York. Michael threw me a lifeline in 1989 for a few years as I worked on many of his TV specials from Toronto. The one I contributed the most to was Mike Mulligan and His Steam Shovel, animating about a quarter of the film. Looking back on my career, my work for Michael is easily some of my favorite. He was a hands-off director, giving me more freedom as an animator than most other studios, and yet the resulting films always bore his stamp.

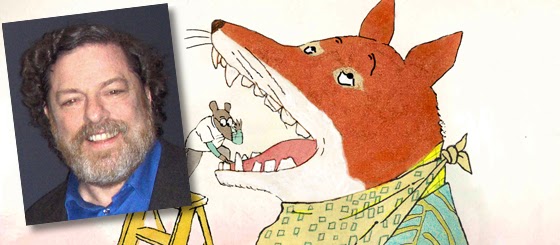

Michael’s budgets were always low. The animation I did for him had to be on three’s in order to stay within the budget. Working for cable channels or PBS, it was a given that budgets would not be as high as those from the networks. However, the freedom these outlets provided allowed Michael to make films that he cared about. The Red Shoes, Happy to be Nappy and Whitewash all dealt with race. The Little Match Girl dealt with urban poverty. Abel’s Island, based on a book by William Steig, dealt with loneliness and the power of art. That film and other Steig adaptations, Dr. Desoto and The Amazing Bone, are far more faithful to Steig’s work than DreamWorks was.

Michael always wanted to make a feature. He came close several times. His final project, based on Edgar Allen Poe, was plagued by problems; first the death of Tissa David and now Michael’s own. It's ironic that Michael passed away on January 19, Poe's birthday. At a time when animated features are proliferating, it’s a crime that Michael never had the opportunity to make one. His uncanny ability to stretch a dollar meant that he could have made a feature for under $5 million, but because he stuck with drawn animation and because his taste was considered too different from typical animation, he never got the chance.

For all the box office and ratings success that animation has enjoyed recently in North America, I would not call this a fertile time. Too many films and TV shows are imitating past successes. Michael never gave in, though it probably would have been to his economic advantage to do so. He managed to keep his studio going, always looking for projects he could love despite their tight budgets. He stayed in New York, he stayed true to his own vision, and he provided opportunities for artists that nobody else would. He took advantage of New York’s cultural scene by hiring actors and musicians from the theatre for his projects, tapping a talent pool that Hollywood has mostly ignored. He made good films. My favourite is Abel’s Island, though they all are worth watching.

Michael’s lack of profile with the general public will make his loss seem less than it is. Make no mistake: we’ve lost a great film maker who managed to create art with the sparsest of resources. Animation needs creators like Michael if it’s ever going to explore the full range of human experience.

Those who knew and worked with him know what we’ve lost. I’m sorry for those who aren’t aware of Michael’s work, but while they can correct that, they missed the chance to know a great animation artist and a generous friend.

No comments:

Post a Comment